By Fiona Meagher, Year 12

Warning: this article is specific to English-language TV

Streaming has become the dominant form of television and entertainment. The growth of streaming platforms has hugely expanded the capacity for TV production and improved the accessibility of television worldwide. However, this accessibility comes with the risk of companies – and, by extension, audiences- conflating art forms such as movies, television and music with the general notion of ‘content’, pumped out into the internet at speeds and in quantities unimaginable to humans even two decades ago.

Video-on-demand streaming services originated with Netflix, which transitioned from a video rental service in 2007. Today, it has over 282.7 million users worldwide, making it the first and most popular streaming platform. Netflix’s unique model of acquiring and, since 2013, releasing original television, has completely transformed how popular television is produced and consumed.

Netflix’s release of House of Cards in 2013 was a major first for Hollywood: it had a budget of $100 million, was produced for a streaming service, and was released onto the platform all at once. This averaged out at a budget of nearly 8 million dollars per episode, when the industry maximum for a show not requiring science-fiction or fantasy effects/production was around 2-3 million per episode. This was the novelty of streaming: high-budget series that audiences would no longer have to wait weeks to watch, instead being able to consume at a chosen pace.

In short, this defied expectations and resulted in huge success. Netflix’s first original series, House of Cards and Orange Is The New Black, were nominated for 9 and 12 awards respectively at the 65th Emmy Awards. In 2014, Netflix reported $5.5 billion in revenue, a 127% increase in revenue from the year before. This success of Netflix’s ‘originals’ meant this format became commonplace for modern TV, especially with the launch of other streaming services like Prime Video and Hulu in the late 2000s, followed notably by Disney+ and HBO Max among many others in the 2020s.

Although they have been popularised, shorter, 6-13ish episode seasons aren’t new or exclusive to streaming. While US and Australian broadcast programmes typically had 20-30 episode seasons, shorter format has been the standard for TV in the UK and Ireland. Shorter first seasons were also common for many U.S. network series that later expanded, such as Parks and Recreation, The Office, and Seinfeld, while some popular network shows maintained short seasons throughout their runs. In short, this isn’t inherently problematic- series can still and always have been able to complete arcs within 8 45-minute episodes.

But there’s no one-size-fits-all for television shows. For every House of Cards or Breaking Bad– both of which managed stellar ratings despite having a combined 3/10ths of the current total episodes of Grey’s Anatomy- there are stories that simply can’t fit within these constraints, which more often than not, leads to underdeveloped and rushed storylines. Or, marginally less frustratingly, leads to showrunners being forced to write two-and-a-half-hour-long episodes in order to complete arcs within Netflix’s episode constraints. This leads us to one of Netflix’s biggest and it’s most confusing property: Stranger Things.

Stranger Things’ first season was first released in 2016, receiving a 92% on Rotten Tomatoes and breaking many records: 40.7 million households watched the show in its first four days. The fourth season was released in 2022, with a budget of $30 million per episode. This means that one season of the show cost 270 million. For reference, that is 270% the budget of Oppenheimer, last year’s winner for Best Picture.

This is a constant and concerning pattern with Netflix and most other streaming services: spending colossal amounts of money on seasons of television shows and cancelling them unless they massively break records of viewership. Disney+ spent upwards of $230 million on The Acolyte, which was released from June to July 2024. It received generally good reviews, with 78% on Rotten Tomatoes, however was promptly cancelled in August of 2024. There were several online movements to renew it, including a Change.org petition with more than 50,000 signatures, to no avail. Disney also spent $465 million on Lord of The Rings: The Rings of Power (58 million dollars per episode), meaning it had a higher budget than the most expensive movie of all time, Star Wars: The Force Awakens, which cost $447 million. While it’s currently unconfirmed whether The Rings of Power will receive a third season, it highlights studios’ willingness to spend baffling amounts of money on a show’s production while failing to adequately pay their workers.

Because of these ridiculously high budgets, these platforms refuse to allow the creation of more than 10 episodes per season, which results in the aforementioned two-hour-and-a-half-long episodes, such as season 4 episode 9 of Stranger Things. How that isn’t a red flag to studio executives that they need to greenlight more episodes is utterly incomprehensible. Further, since they are released all at once (or worse- in two batches released months apart from each other) it completely lacks the opportunity of watching a story unfold little by little with a community of fans, and instead feels more like watching an 8 hour long movie. And because Netflix refuses to release weekly, the well of profit of shows and movies runs dry within days or weeks, which is another primary reason that subscription costs are raised, and workers and creators underpaid.

As demonstrated by The Acolyte, streaming platforms have a hairpin trigger when it comes to cancelling beloved and/or well supported series within one season unless they entirely defy expectations. At the least, Netflix’s original success stories, House of Cards and Orange Is The New Black, were able to make it to 5 and 7 seasons respectively. While certain shows such as Wednesday, Squid Game and, as previously mentioned, Stranger Things, broke records with their first seasons, many critically acclaimed and successful shows have had poorly rated first seasons. As a result, they would never have been able to reach their potential had they been produced by modern streaming services- examples include Parks and Recreation, Buffy The Vampire Slayer and The Office. There have been countless fan movements to renew the seemingly infinite amount of shows cancelled by streaming services after one season despite being well-received. Notably, recent series like Kaos, starring Jeff Goldblum, which was cancelled by Netflix within 2 months of release, and Dead Boy Detectives, also cancelled by Netflix within a few months despite having an extremely dedicated online fanbase. The Society, Inside Job, Shadow and Bone, Anne With An E, Lockwood and Co., Everything Sucks, The OA– the list goes on. Netflix doesn’t care about art, quality, or giving shows time to develop, nor does it bother to properly promote them. (There is also a noticeable pattern of quickly-cancelled programs being centred around women and minorities). It’s unmistakeably profit-first, exclusively concerned with the bottom line. This is why exceptional, record-breaking cases and trashy reality series are unique in being renewed- Netflix has no intention of supporting artists or rewarding audience support.

Finally, on the topic of Stranger Things, when the fifth and final season airs in 2025, it will have totalled 5 seasons in 9 years, which is absolutely laughable when compared to network runs, even in the category of sci-fi and fantasy. Supernatural, despite the 2008 writers strike, aired 15 seasons in as many years. Lost, similarly, did 6 seasons in 6 years- both having a fraction of Stranger Things’ budget. While Stranger Things manages significantly better reviews and objectively superior quality, it exemplifies how much studios like Netflix demand from fan bases and their overall lack of productivity even in projects they invest the most in.

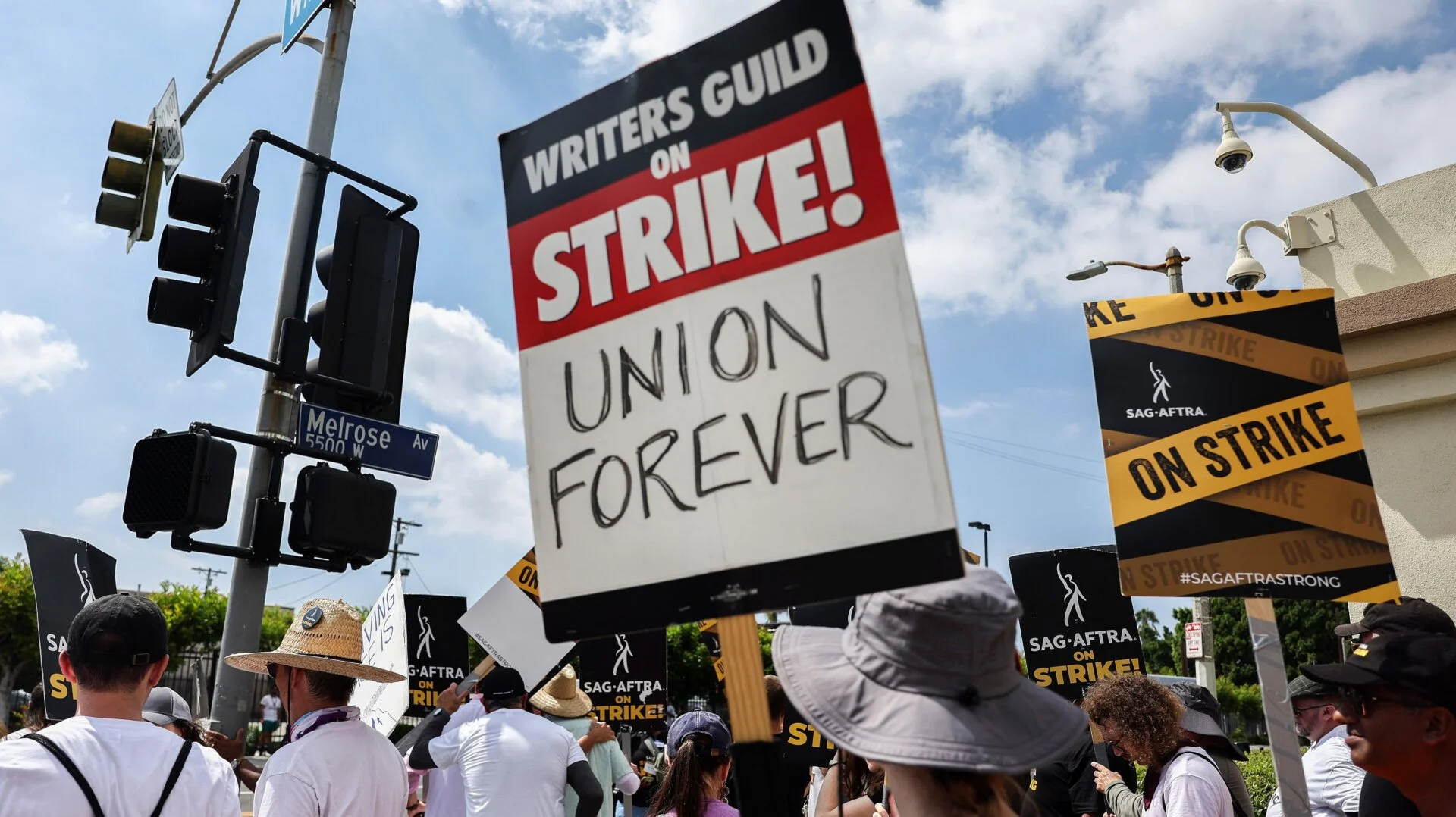

Another major, 148-day-strike-causing issue is that the streaming television industry grossly underpays its workers to the point that any incentive to produce actual quality television is depleted. While streaming platforms are busy spending more money than most people see in their lives on single episodes of television, their writers are left without benefit from any triumph their work sees. In the case of broadcast television, a major source of income for writers, producers, actors and others is residuals: financial compensations when content they worked on is syndicated, put on DVD or re-aired. Writers especially were able to earn money when their series saw success and managed to bring a larger audience to the network, or anytime episodes were re-run. In the case of streaming, there are (tragically) no DVDs, and obviously no reruns. Writer-producers are paid, (reportedly 23% less than a decade ago), to make something and effectively release it into the void, never receiving any more payment for it regardless of its success. Even if you, as a writer, wrote the best and most accomplished show in television history, bringing thousands of new users to the streaming platform with the sole incentive of watching your masterpiece, you wouldn’t have seen any additional compensation for it. What does this do for artists writing television? It’s completely demoralising- it effectively doesn’t matter whether or not your work has lasting value or connection to audiences. Either way, you would stay poor, and either way, Netflix would continue making seasons of Love Is Blind.

Writers aren’t exclusively hurt by this- actor Mark Proksch spoke out last July, during the 2023 actor’s strike, stating that he made more from only residuals from The Office than from every season of FX’s What We Do In The Shadows combined, despite appearing in 19 episodes of the former and 59 episodes of the latter. The SAG-AFTRA strike wasn’t the first of conflicts between actors and streaming platforms: in 2021, Scarlett Johannson sued Disney+ over the complete lack of streaming residuals she received from Black Widow, despite Disney prioritising its launch on its (at the time) new streaming platform over its time in theatres. While details of the settlement are unconfirmed, Johannson reportedly received over 40 million.

Under the streaming model, everyone is expected to give more, while receiving less in return-fans, actors, writer-producers and all the workers involved. Since the end of SAG-AFTRA and WGA strikes of 2023, writers and actors reportedly receive streaming residuals and protection against use of AI. However, the CEOs of streaming companies remain billionaires while workers in Hollywood continue to be unable to pay rent. Furthermore, the effects of the streaming model on television remain prevalent: event network shows now struggle to get renewed for more than 13 episodes. In conclusion, television shows are legitimate forms of art that develop genuine connections with their audiences- demonstrated by the efforts of ‘fandoms’ to get their favourite shows renewed- and deserve the respect that title commands, not to be pumped out and immediately cancelled by streaming services merely attempting to improve their stock prices.