If Dawkins’ original goal was to persuade religious people to recognise the weaknesses in their faith, then I suspect this book would divide and enrage rather than unite.

By Qingyang Zhang, Y 12

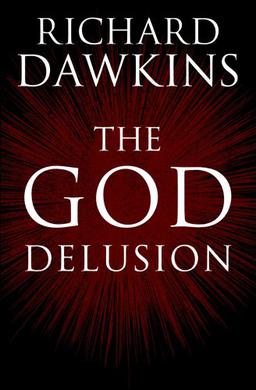

I picked up Richard Dawkins’ book The God Delusion in a bookshop in Paris, when I was traveling. Having read Dawkins’s book The Blind Watchmaker, I knew his self-righteous writing style and rational perspective. I was thus curious to see how he would apply scientific theory to a complicated matter, religion.

Richard Dawkins begins his book by presenting statistics demonstrating that Americans, and the world population in general, are becoming less religious. Although I cannot find the studies Dawkins refers to, I found a peer-reviewed journal article on American adolescents’ religious inclinations which confirm his claim that American adolescents are less religious than previous generations. Focusing on a monotheistic approach, Dawkins defines God as the “supernatural creator…appropriate for us to worship”, and states his overarching hypothesis that God is a delusion.

Dawkins presents frequently used arguments for God’s existence and then proposes counterarguments. For example, he addresses the teleological argument, where a “watchmaker” must have carefully crafted our biology in order for circadian rhythms to function with such precision. Dawkins then dismisses the need for a complex designer by invoking the theory of evolution.

Interestingly he then also rationalises the existence of religion by applying the theory of evolution. He sees the proliferation of religion throughout generations as the by-product of children being obedient (which is an evolutionary strength). Dawkins moves on to address the argument that religion is justified even if God doesn’t exist, on the reasons that it provides moral code, comfort, and inspiration. Dawkins then refutes those claims by citing examples of the bible teaching values which we commonly regard as immoral. He also deals with the issue of children being manipulated by religious authorities.

Overall, the book is academic and formal, but still relatively easy to read. Dawkins does a good job of bringing the reader along with his arguments.

My issue with the book is Dawkins’ assertive tone. For deeply religious people, the book might not be a welcoming call. Dawkins has a tendency to use straw-man fallacies by generalising groups of people. He does not discuss the good done by religious people in the name of religion.

Nonetheless, I personally am a big fan of Dawkins’ scientific treatment of religion and his emphasis on rationalism. It provides a different approach, since religion relies on oral tradition, whereas the scientific method is quantitative and reproducible. The methodology of the two fields seems to be incompatible. However, Dawkins rightly points out that there should be more interface between religion and science.

Richard Dawkins’ The God Delusion is available in the LGB library. If you do not want to read the book, you can also watch the documentary The God Delusion hosted by Dawkins himself.

I would recommend the book to philosophy, history and biology students, as it provides knowledge and a critical viewpoint on evolution and religion. It is insightful for all critical thinkers who want to explore the reasons people have faith, and the advantages and disadvantages of religion. It can also provide examples for Theory of Knowledge classes.

Reading Dawkins’ arguments also made me appreciate the importance of critical thinking. There is an example of a school in Britain, Emmanuel College, which teaches creationism instead of science. In the scientific paradigm today, it seems obvious to us that what Emmanuel College is doing is ignorant. It is easy to scoff and dismiss it, but we must also consider whether we learn science with the openness and critical thought it needs? Do we accept science like the “new religion”, contrary to the method it hopes to instill?