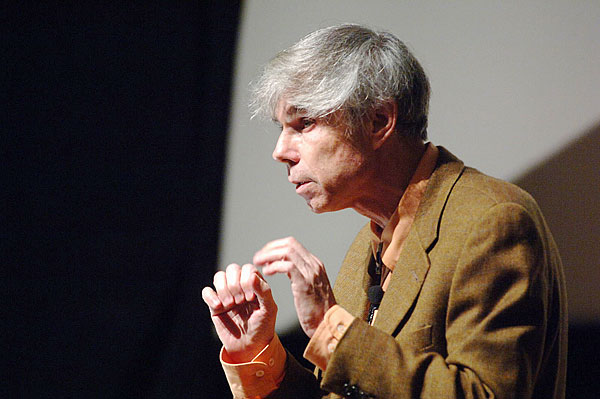

On Monday, June 25th, year 12 students will have the privilege of listening to Professor Douglas Hofstadter speak. While Hofstadter might be unfamiliar to some, he is an eminent scientist, a professor of Cognition (the study of the mind and its processes) and Comparative Literature at Indiana University, a Pulitzer-Prize winning author, and a former student at Ecolint. His research is varied, ranging from errors as a window on the mind, to the mechanisms of creativity, to the nature of consciousness.

Hofstadter has described himself as “someone who has one foot in the world of humanities and arts, and the other foot in the world of science.” In addition to his study of cognitive sciences, Hofstadter is also passionate about languages. In addition to English, his mother tongue, he speaks French and Italian fluently. At various times in his life, he has studied German, Russian, Spanish, Swedish, Mandarin, Dutch, Polish, and Hindi.

One way that Hofstadter’s love of languages can be seen is through his enthusiasm for translating, especially poetry. Hofstadter argues that translation is a uniquely human skill, as meaningful translation requires “creating a text in a second language that is equally good as the text was in the original language. So if the text in the original language was artistic and beautiful, then the text in the second language should be artistic and beautiful in the same manner.”

One of Professor Hofstadter’s favorite poems to translate is “À une damoyselle malade”, by 16th century French poet Clément Marot. The poem was written to an ailing, seven-year-old princess, urging her to get well. Hofstadter describes the poem as “wonderfully mellifluous and graceful.” In 1997 Hofstadter wrote a book, Le Ton beau de Marot, that centers on 88 varying translations of this poem.

In anticipation of his visit next month, Professor Hofstadter has presented the Ecolint community with the following challenge (in his own words).

It has to do with a small but very subtle poetry-translation challenge that I set myself back in 1987 and proceeded to solve once, twice, then three times, four times… and before long, the whole thing had taken off in a veritable explosion of brand-new poems coming not only from my own pen, but from the pens of my friends, my students, my relatives, my colleagues, and then the pens of people all over the world. The challenge was to translate into English the following poem by Clément Marot:

À une damoyselle malade

Ma mignonne,

Je vous donne

Le bonjour.

Le séjour

C’est prison.

Guérison

Recouvrez,

Puis ouvrez

Votre porte,

Et qu’on sorte

Vitement,

Car Clément

Le vous mande.

Va, friande

De ta bouche,

Qui se couche

En danger,

Pour manger

Confitures.

Si tu dures

Trop malade,

Couleur fade

Tu prendras,

Et perdras

L’embonpoint.

Dieu te doint

Santé bonne,

Ma mignonne.

My self-imposed challenge, way back in 1987, was to respect equally faithfully both the form and the content of this miniature and catchy gem (which I had fallen in love with and memorized when I was 16 years old). This form-plus-content challenge entailed respecting the following eight constraints:

(1) using exactly three syllables on every line;

(2) making the stress fall always on the line’s final syllable;

(3) making the total number of lines equal to 28;

(4) using rhyming couplets throughout (AA, BB, CC,…);

(5) making the first line identical to the last line;

(6) having the poet self-refer toward the middle;

(7) switching over to a more intimate tone roughly halfway through (since the French poem starts out with “vous” and changes over to “tu” toward the middle);

(8) making the translated poem consist of semantic chunks of two lines apiece, always out of phase with the rhyming couplets (in the original, the so-called “semantic chunks” are as follows: “je vous donne le bonjour; le séjour c’est prison; guérison recouvrez; puis ouvrez votre porte; et qu’on sorte vitement; car Clément le vous mande”, etc.).

(Above, I put constraint #8 in bold, because to respect that constraint, in addition to the other seven, is exceedingly tricky, and is certainly not for beginners; in fact, to respect it is very hard even for seasoned poetry translators.) I think you will agree that this small but difficult translation challenge has everything to do with showing respect for, and indeed being intoxicated with, structure and pattern.

This is really an exercise on variations on a theme on quite a grand scale (although the theme itself is quite small). Almost no experience in my life was ever as enthralling to me as translating this poem over and over again, and thereby producing small new rhythmic and rhyming “linguistic nuggets” — usually in English, but once in a while in other languages. (Years ago, I did a couple of translations into Italian, and also a couple into modern French, as well as one in which English and French alternate from one line to the next.) Once I had launched myself down this pathway, in 1987, I remained deeply plunged into this obsessive activity for many years, and even today, 30 years later, I am still succumb, from time to time, to the temptation to do it yet once again, always in a novel fashion.

I would thus propose to the student body of Écolint as a whole the same challenge: namely, to carry Marot’s little poem over into English, or into one’s own native language (or into a language in which one has native or near-native mastery), while respecting the eight above-stated formal constraints (or at least the first seven of them). The result should ideally flow as gracefully and as melodiously as the original, and should ideally express the same sentiments, although some liberties can of course be taken, since true art always involves novelty and unpredictability. (I’ll never forget my mother’s wonderfully spontaneous solution to the challenge, which was so off-the-wall, so in-your-face, so out-of-bounds, so totally idiosyncratic and zany, that I was completely dumbfounded, and yet hers became one of the top favorites in the collection published in Le Ton beau de Marot.)

So, there you have it, a challenge that is, according to Dr Hughes, “other-worldly, subtle, beautiful and diabolically difficult.” If you are interested in accepting this challenge, you can email your translations to Ms Kretzmeier (angela.kretzmeier@ecolint.ch), no later than 12h00 on Friday, June 15th. Responses will be forwarded to Dr Hughes and then Professor Hofstadter. Professor Hofstadter will read the translations and mention the most effective ones during his talk on June 25th.